“It is an enchanted castle,” said Gerald in hollow tones.

[…]

“But there aren’t any,” Jimmy was quite positive.

“How do you know? Do you think there’s nothing in the world but what you’ve seen?” His scorn was crushing.

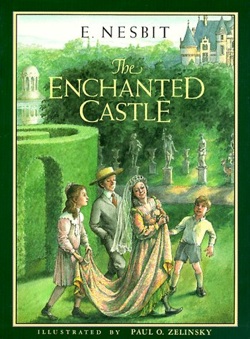

After the realism of The Railway Children, Edith Nesbit decided to return to the worlds of magic and fantasy and wishes that go quite, quite wrong. It was a wise choice: loaded with sly references to other fairy tales, books and history, The Enchanted Castle, despite some awkward moments here and there, is one of Nesbit’s best books, consistently amusing, with just a hint—a hint—of terror for those who need to be just a little bit frightened. (In my own case, this made me read eagerly on.) If for some reason you still haven’t picked up a Nesbit novel, this is an excellent place to start.

Like some of Nesbit’s other novels, The Enchanted Castle begins with three children facing nearly guaranteed boredom during a summer vacation from school. Fortunately, some mild trickery allows them to spend their summer holidays, right near Castle Yardling, with its elaborate and delightful gardens and fairy tale atmosphere. Since the three children, Gerald, Kathleen, and Jimmy, were already deep into a game of Let’s Pretend (Gerald adds to this by almost constantly framing himself as a hero from any of a number of popular books), they have no problem falling into the fantasy that they have just found an enchanted princess in the castle garden.

They do have a few more problems once they realize that although the princess may not be quite enchanted, something in the castle certainly is.

Nesbit repeats many of her beloved themes here: wishes can go spectacularly wrong; explaining adventures to skeptical adults can be difficult indeed; magic is less enjoyable than you would think, especially when you are having to deal with its various unexpected effects. (In particular, going invisible, getting taller, and having, to follow half monsters through downtown London to save a sibling, when you’re hungry.) Her children in this case have decidedly more distinct personalities than any she had created since the Bastable books, and, although I rarely say this, it’s entirely possible that a few of them might have done just a little too much reading. Gerald, the oldest, happily narrates—out loud—the adventures the children are having, to their exasperation; Kathleen makes several assumptions based on the tales she has read, and on her very real desire to find out that magic and stories are real. Jimmy is considerably less adventurous, and wants to make sure that nobody forgets the food; and Mabel—whose identity I shall leave you to discover—is able to cheerfully rattle off stories based on the various books she’s read, adding her own highly imaginative touch—an ability that turns out to be quite helpful indeed.

Once again, Nesbit cannot resist leaving economic issues out of her fantasy, although in this case, she is primarily concerned with the issues of the very upper class, and her economic discussions are considerably toned down from earlier books. The owner of the castle, a certain Lord Yardling, does not have enough money to actually live in it, or marry the woman he’s in love with, and is therefore thinking of renting out the castle to a wealthy, gun-toting American—an echo of the very real wealthy Americans that happily bought or rented out castles or married aristocrats in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. A passage dealing with some hideous Ugly-Wuglies allows Nesbit to take some well-aimed shots at British upper class society and the investor class. And once again, Nesbit shows women needing to make their own living—Mademoiselle, who thanks to cheating relatives and bad investments has been forced to begin working as a teacher, and a housekeeper needing to support a young niece, creatively finding ways to stretch money and cleaning supplies.

I found myself distracted by some small unimportant matters—Nesbit’s insistence on spelling “dinosaur” as “dinosaurus,” or the rather too fast awakening of the Ugly-Wuglies, a passage I generally have to reread a couple of times on each reread just to remind myself of what is going on. And I’m decidedly unhappy with the characterization of Eliza, a stereotypical dull-witted, not entirely trustworthy servant mostly interested in her young man. Much of that unhappiness stems from having to read far too many similar descriptions of British servants of the time, written by their very superior employers, and it tends to grate after awhile. Especially when, as in this case, the character is penned by a writer all too familiar with why women entered servant positions, and who elsewhere showed sympathy, if not always understanding, of the lower classes.

But otherwise, this book, with its laugh out loud passages, is one of Nesbit’s very best. And for sheer fantasy, Nesbit was never before or later to equal a glorious passage where the marble statues of the garden come alive, inviting the children to a strange and dreamlike party. Try to read it if you can, preferably in a pompous British accent (the bits with the Ugly-Wuglies are particularly effective that way.)

Incidentally, I haven’t done much comparison between Edith Nesbit and L. Frank Baum so far, even though I should: they were both highly popular and inventive children’s writers working at about the same time who helped establish and stretch the world of fantasy literature. (Nesbit began a little earlier, but both were producing children’s books at a frantic rate in the first decade of the 20th century.) Although Nesbit focused on economics, and Baum slightly more on politics, neither hesitated to slam the social, economic and political structures of their day. And both used humor and puns to create their worlds of magic.

But The Enchanted Castle also reminded me of some significant differences. For one, Baum rarely used families and siblings in his work, instead focusing on the adventures of individual children who met up with strange and bizarre companions along the way. (Exceptions include Queen Zixi of Ix and, I suppose, the books featuring Trot and Cap’n Bill, who have turned themselves into a family.) His protagonists rarely engaged in games of Let’s Pretend; then again, his protagonists rarely had time, as they were almost immediately swept into fantastical lands and adventures within the very first chapter. Nesbit introduced her magic more subtly.

But perhaps most importantly, Baum featured magic, magical items, and wishes as generally beneficial. Certainly, they could be misused by the more evil or misled characters, but for the most part, magic provided solutions and made life easier for the characters. Fairyland and magic, in Baum’s world, is delightful.

Nesbit still finds the delight in fairyland, but not in magic; her characters almost always find that magic causes more trouble than its worth, no matter what they try to do with it. By the end of each book, Nesbit’s characters are often thankful to be giving up magic, no matter how delightful some of these experiences have been. (In including, in The Enchanted Castle, an extraordinary moment of talking to and eating with living statues beneath a shimmering moon.) In Baum, the characters leave fairylands only because they have homes they must return to; in Nesbit, the characters may regret losing their adventures, but are just as glad they don’t have to deal with all of that troublesome magic.

This is partly because Baum’s characters generally leave home, while Nesbit’s characters frequently have to deal with the aftereffects of magic (and explaining these, and their disappearance, to unsympathetic adults), and partly because Nesbit’s characters typically come from considerably wealthier backgrounds. But I think partly this has to do with their personalities. Baum, cynical though he could be, was an optimist who, if he could not exactly take joy in churning out endless Oz books, could take joy in the opportunities they brought—including filmmaking and stagecraft. While Nesbit saw her books bring her steady income and a certain level of fame, but very little else, leaving her always aware that magic most definitely had its limitations.

Mari Ness has never stopped wondering if statues really do come out and dance beneath the moon when humans aren’t around. She lives in central Florida, where the only statues who do this are in comedy shows at theme parks.

I didn’t read this book until I was an adult, but it’s one of my favorites.

I like the comparison between Baum and Nesbit. I think part of what’s going on there is that, as modern writers, they’re doing very different takes on the nineteenth-century tradition of fairy tales and fantastical writing. Nesbit’s a much more naturalistic writer than Baum; Baum’s writing is very self-consciously fairy-taley in a literary sense, especially when his stories are set in recognizable American settings, as in American Fairy Tales. Baum’s fantasizing reality; Nesbit’s making fantasy seem realistic. I think that goes along with what you say about their attitudes towards magic.

Baum’s writing is like a modern cartoon of a fairy tale–in fact, like John R Neill’s illustrations. Nesbit’s writing feels more to me like a photograph with something strange about it, like those fairy photos that confused Arthur Conan Doyle.

Most of E. Nesbit’s books (or perhaps all of them — I haven’t checked) are available FREE at Project Gutenberg or manybooks.net. The article links only to Barnes and Noble, which is charging $.99 for the ebooks. Suggest that in the future, all links to books include the free alternatives as well.

@seth e — I’m going to be going into this more in some upcoming posts, but an additional factor, I think, is that Baum worked mostly independently as a writer, while Nesbit was socially part of a literary movement that included a science fiction writer who used science fiction as social criticism, and a realist playwright who later headed off to socialize with Stalin (we’ll get there). Nesbit naturally wanted her friends to admire her work, and this became both a constraint and something she occasionally protested – as in Wet Magic.

Poor Arthur Conan Doyle :( The death of his son really hit him hard.

@DPZora – Thanks for your comment. Tor.com and Barnes and Noble teamed up just a short time ago to showcase fantasy fiction, thus the Barnes and Noble links. BN.com does have some Nesbits available for free download (The Wouldbegoods and some of the poetry collections, which I won’t be reviewing here) .

By the way, since they’re in the public domain, you’d think that most of Nesbit’s books WOULD be available for free online, wouldn’t you, but alas, no. Her children’s books, generally yes (with one exception: The Five of Us and Madeline), but her adult books and short story and poetry collections, not so much. Oh well.

Mari, I know you aren’t running short of projects by any means, but this post reminded me of my favorite author as a child, the wonderful Edward Eager. I’d love to revisit them as an adult — any chance of a re-read?

@hapax — I’m happy to tell you that Edward Eager is already on the agreed upon list! When precisely I’ll be covering him, I’m not sure, but he’ll definitely be reread eventually.

YAY!!!

I have fond memories watching a televised adaption of this book in the early ’80’s when I was a kid. :)

You’re right that this is an excellent place to start; it’s the first Nesbit I ever read, lo these many moons ago. The statue scene definitely revved up the sensawunda & got me all “wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey” before I knew what that was.

@jan the Alan Fan – I have been hearing excellent things about many of the Nesbit television adapations — I’m starting to think I need to check it out.

@filkferengi – The statue scene is really beautifully done — possibly Nesbit’s best work ever. (But I may be prejudiced by my childhood love for that scene.)

I’ve never read anything by Eager. OTOH, it was only a few years ago that I read my first Nesbit (this one, because someone had suggested it was a possible source for Tolkien’s ring) and I only read some L’Engle last year. So, Hapax, Mari, or anyone – is Eager the kind of writer you can read for the first time as an adult, and get anything out of? And if so, Where Do I Start With That?™ (Though Jo Walton had no firm opinion on the subject in her post on authors beginnning with E!)

@@@@@(still) Steve Morrison – It’s been a long time since I’ve read anything by Eager, so I have no idea where you should start. My plan is to do the books in publication order, although a quick check has shown that I may have to skip his first three books and just focus on the Magic series, since those seven books are readily available seemingly everywhere, while the first three books seem to be very much out of print. We’ll see.

And L’Engle should be up next, barring any need for a fill in post.